Free shipping on all US orders

10% OF OUR PROFIT GOES TO KIDS’N’CULTURE NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION

Hans Op de Beeck is a multidisciplinary visual artist of Belgian origin, widely recognized for his large-scale installations and sculptures, distinguished by their signature monochrome grey palette. His works invite viewers to step into a parallel, silent world, offering a new sensory experience — one that, as the artist himself puts it, seeks to touch the essence underneath the skin of reality.

Op de Beeck masterfully balances between reality and abstraction, tragedy and comedy, light and shadow, transforming the ordinary into something almost magical. His sculptures capture life as if suspended in time, evoking reflections on existence, mortality, solitude, and the fleeting beauty of the moment.

Working across a wide range of media — from painting and film to photography and text — Op de Beeck remains committed to one guiding principle: art should resonate on multiple levels. It must be accessible to all while holding deeper layers of meaning for those willing to look beyond the surface.

The Quiet Parade

Vanitas XL

I first encountered your work at the Art Basel art fair in Paris, back in 2022. The only piece that made a strong impression on me that day was your sculpture ‘Danse Macabre’. I was amazed by the intricacy of its execution and the special soft grey coating you applied to the sculpture, which in my mind evokes associations with dust or ashes. Could you tell me a bit about the choice for this color and your unique technique?

Over the past decade the part of my work that I executed in monochromic grey has gotten the biggest exposure, so it is more known than works I executed in different tones. I did make quite some full colorsculptures or sculptures in combinations of two or three colors, and most of my video works and scenography for theatre and opera are in full color…

But at some point, in my production, I discovered my own kind of grey, that makes sculpted objects, interiors or landscapes appear as if they are fossilized, made of stone or pigmented plaster. This petrified aspect makes one think of Pompeii: life frozen in time as it were. I discovered that the grey coating I almost coincidentally invented -a technique of layering many thin coatings onto the sculpture- has an almost velvet like appearance that reflects the light very tenderly. In my view, it gives a special aura to the depicted, a soft skin that abstracts the figurative forms into a kind of a parallel, silent world. The absence of color puts the focus on the light. Throughout my work, light and how it reflects and animates, is of extreme importance, since it totally defines and articulates the mood of an image, regardless the medium.

My work is never about simulation of reality as it is, not about literal mimesis or imitation, but about evoking a mood, interpreting, and abstracting the world to touch the essence underneath the skin of reality. I want to evoke a mood, a form of visual, sensorial fiction that the viewer can identify with and experience before understanding it. My works in monochrome velvet grey, in black and white, or, say, in light blue and soft green, are silent, concentrated variants on what we know. That is why I do not work with ready-mades: my sculptures and installations, which are often hundreds of square meters in size, are made by hand, because of the power of interpretation.

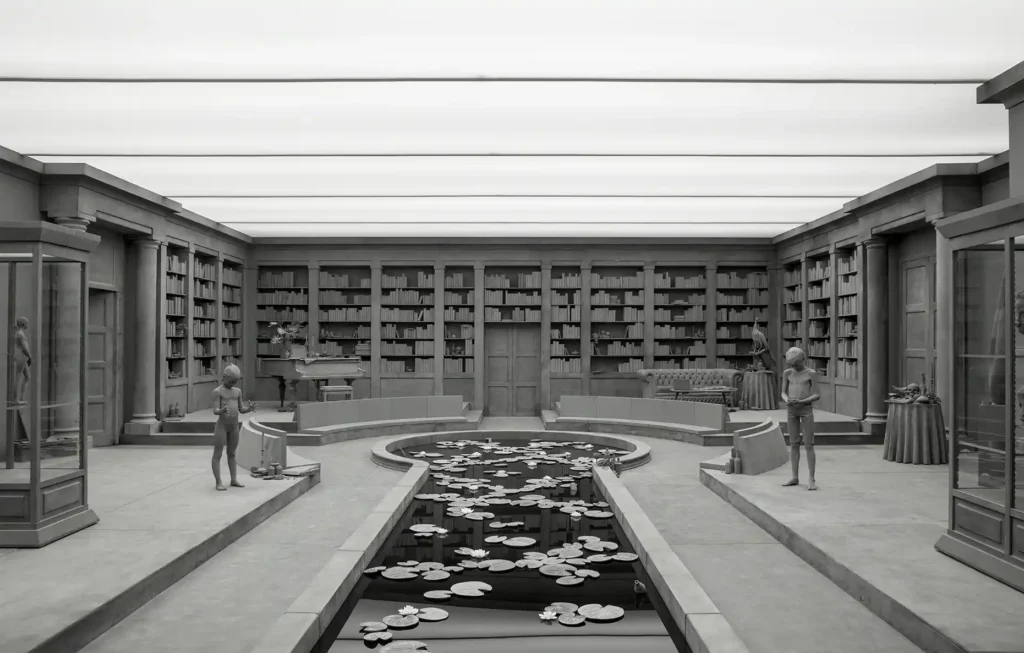

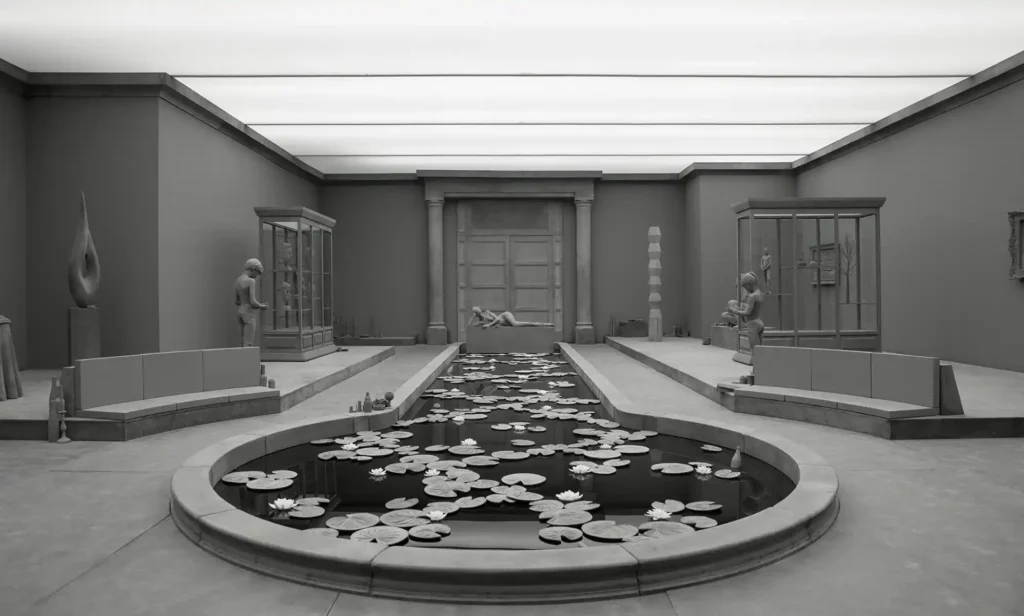

The Collector's House

A good example of the effect of this soft grey skin on an immersive scale, is my installation ‘The collector’s House’ (2016), a work of about 250 m2.

The viewer here enters a black and white, neoclassical evocation of a large hall of some 240 m2, like a Wunderkammer-like lounge with a grand piano, a sort of library with an extraordinary art collection of sculptures, paintings and a salon with a large water lily pond for contemplation.

The sculptures, furniture and huge quantity of books are entirely made of plaster, wood, polyester and glass, as if everything has turned to stone. The fictional space, with its countless eclectic, art historical, filmic and literary references is in the first place a staging of a charged atmosphere that triggers the senses.

Since visitors enter the space wearing their clothes, which tend to be brightly colored, they create a curious contrast with this completely black and white world, as if they are the only dynamic subjects in this arrested universe.

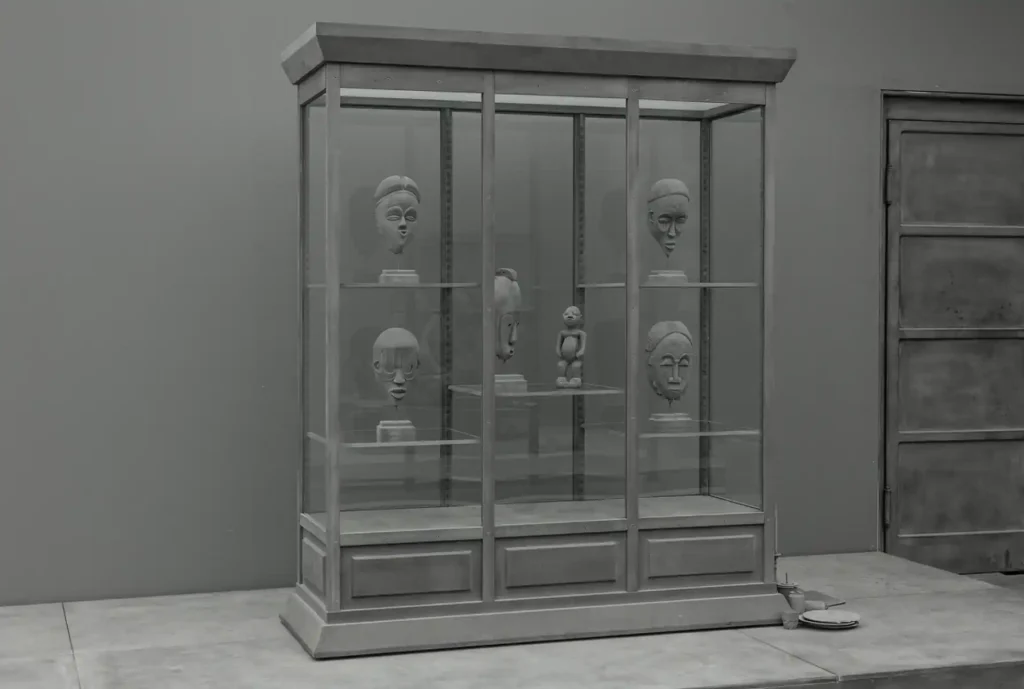

One can quite easily imagine the collector of the title was a man or woman with a megalomaniac streak. The interior’s naïve symmetry has something gaudy to it, and the sculpted figures, the abstract sculptures and paintings, the African looking masks, jugs and discarded cups of soft drink, the full ashtrays and empty pizza boxes attest to a taste that is both poor and good, and order and chaos.

The Collector's House

One of the things the work does is weigh the status of the collector’s item. Although one could claim this installation – with its title and references to art and culture – in a first instance is a work about art itself, my sense is that it mainly addresses man’s predilection for staging and collecting in general, and how he tries to visualize an identity in front of others: his visitors, his circle of friends. The library, filled to the brim with books, is a case in point. Some collectors with means have impressive art libraries that are rarely if ever consulted yet are kept as a means of feigning erudition. In this work the books are also literally illegible: they are made of plaster, closed, sculptural artefacts. This blind library is a contradictio in terminis, like the sculpted grand piano; it is an instrument that produces no sound.

Many other objects in this work also have a double-barreled status. Some of the life-sized figures refer to the classical nude from the long tradition of sculpture, but are wearing headphones, a pair of jogging pants or jeans, or have as their prop an ashtray, a cup of soft drink or a mobile phone.

The large water lily pond central in the space at first looks like a water lily pond. But alongside it the viewer discovers wooden crates in which more water lily leaves and flowers are neatly stored. From this it can be surmised that the pond is also an artwork in the fictional owner’s collection. The pond is in that way the representation of a pond, or, if you like, representation squared.

The Collector's House

There is also a typically nineteen fifties sculpture in the installation, a large, abstracted flame. But on the sculpture’s plinth there is also a sculpted ashtray with cigarette butts. The question could then be: ‘Was the ashtray left behind by the son of the family who had a party in the space housing his father’s collection the night before, or is the sculpture a contemporary sculpture of which the ashtray is a part?’ The African looking masks in the display cases are also ambiguous, since they are but fictional evocations.

There is a stuffed peacock on a plinth. At the foot of the Chesterfield sofa is a little sleeping dog. It is not clear whether this is a sculpture, the representation of a stuffed specimen, or a living dog owned that belongs to the suggested collector? The whole installation, made with the essential ambition of creating an immersive experience of an otherworldly mood, also subtly plays on notions of representation.

The Collector's House

You presented a life size version of your merry-go-round sculpture 'Danse Macabre' in Bruges, outdoors, in front of the local Saint Walburga Church, which seems symbolic and recalls the well-known Latin phrase "Memento mori." Could you share what thoughts and associations that work evokes for you?

The ‘classic’ carousel, as we still know it, is usually a baroque, brightly colored and sparkling kitsch object that refers nostalgically to the times of yesteryear, when the attraction had little competition from all the current fairground commotion. The soft grey color of ‘Danse Macabre’ gives the carousel a petrified and inert appearance, as if it were a fossil, frozen in time. By removing all the color, the carousel is stripped of its last layer of vibrancy. Here, it is like a quiet, ash-covered remnant after a major fire.

The title ‘Danse Macabre’ alludes to the halted procession of carriages, horses and objects that refer to death, and -indeed- the idea of the ‘memento mori’.

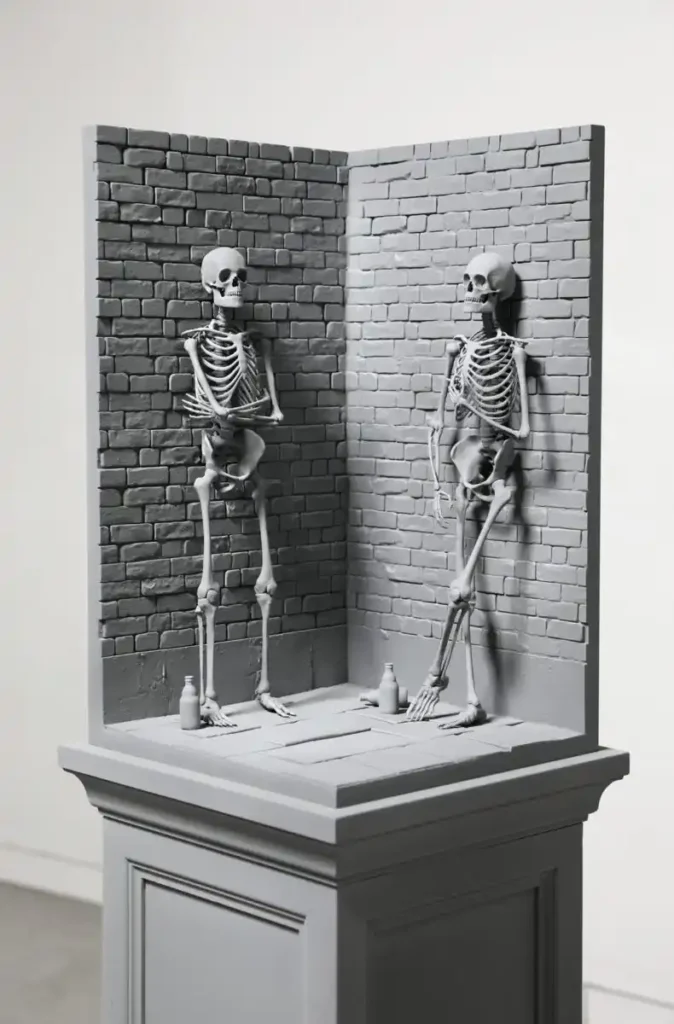

A family of human skeletons populates this tiny carousel: there is the skeleton of a rider who joyfully rides a prancing horse, another skeleton dressed as an elegant lady with a parasol and a long dress, a skeleton of a clown seated in a carriage, smoking a cigarette in a dandy like way, and a skeleton of a shy child who keeps a seal on a leash.

Danse Macabre

These absurd scenes refer to the surreality of the dream, but also the exuberant, festive way in which the Day of the Dead is celebrated in Mexico. Everywhere between the carriages, horses, planes, air balloons and animals, the remains of a party are lying around: empty bottles and glasses, eaten slices of cake and pieces of fruit. This ‘dance of death’ is like a party that has come to a standstill, between a festive memory and a haunting dream.

The positioning of the work next to the church was indeed to bring a kind of inert, discolored joy, a ghostly apparition of a festive object frozen in time into dialogue with the church, where great rituals around birth, suffering and death take place for many.

The ornaments of the baroque facade of the church are also reflected in the festal curls and small angel figures of the carousel.

Danse Macabre

Every artist has their own unique path, and yours has many branches. I know that you not only produce large installations and sculptures, but also films, drawings, paintings, photographs, and texts. Who or what has had the greatest influence on your life and work? What "bricks" did your path consist of?

I am regularly asked about my great examples in contemporary art. Although I admire the oeuvre of many artists who work in a variety of mediums in different time periods, they don’t serve as a starting point.

These days I very much enjoy the tragicomic film oeuvre of the Coen brothers; I admire the economy in the short stories Raymond Carver wrote, and I am enthralled by the mysterious, colorful worlds of the painter Peter Doig. But they are not my ‘examples’. I wouldn’t dare to mirror what I make in their talent; going for being the best Hans Op de Beeck is, to me, more to the point.

Simply put, the inspiration for my work comes to me in everyday life. I am triggered by the way the world reveals itself to me, by what stirs people, and by what moves me. In that sense my work is no meta-art; it is not self-referential – although every work of art does reflect upon its own status, to some extent. At the risk of sounding vague, my work speaks mainly to life, its difficulties, its absurdities and its incredible beauty.

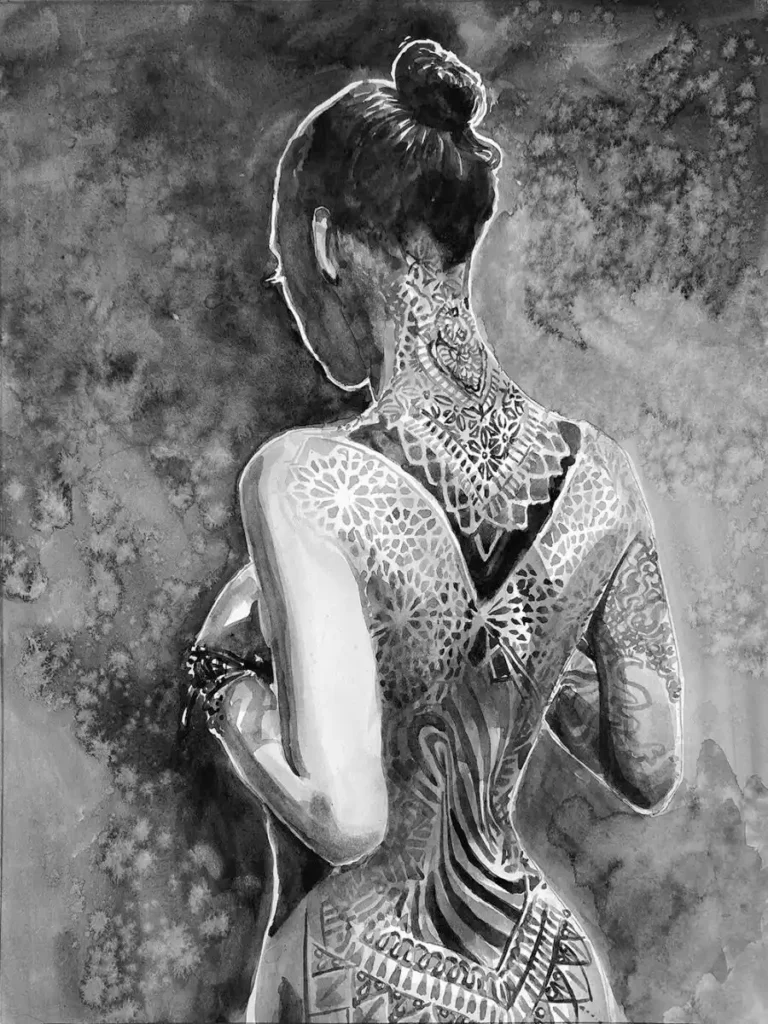

Watercolours

In general, I think the subject of an artwork can be both complex and astonishingly simple. A work of art needs no conspicuously traceable or singular subject. The subject alone is not the artwork, nor is it merely its form. It is the precise, astonishing oscillation between form and subject matter that enables an artwork to come into being, and not the subject, as such. The subject, the initial content, can easily – in a manner of speaking – be nothing. If that nothing is given apt form – as for example in the writing of Samuel Beckett – it can still, as such, result in a resoundingly compelling piece of work.

Now as I am looking at my kitchen table: when does a painting of a few empty bottles, huddled together on a tabletop, become art? If a painter who is not very talented – with all due respect – were to paint them meticulously, they’d just remain bottles, an image with little interest in terms of content. But when Giorgio Morandi would paint groups of vessels, they became a representation of the world. Morandi’s treatment of light, his fragile brushstrokes, his subtle palette, his sense of utter reduction in composition and detail, his palpable concentration and pictorial talent make such an apparent non-event into something wonderful and essential. The mood conveyed through his visual idiom – which can hardly be described in words – turns those bottles into an intensely vibrant presence.

In that way ‘a woman who is looking at us’ could be an accurate, down-to-earth description of the most famous painting in the world: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Merely from the point of view of that description it could be possible to conclude: ‘Content: zero’. If an art student today were to go to his or her painting tutor and say: ‘I would like to paint a woman who is looking at the viewer’, it is likely they would be reprimanded for a lack of ambition in terms of subject matter. But Da Vinci creates content by painting her in such a way that her gaze and smile are intriguing, that the ordinariness of the female portrait is transcended, and that a story occurs, and an experience is possible; it is as if you are meeting her.

Watercolours

Watercolours

When I am in the position of being a viewer, I like to find solace, peace and an invitation to contemplation in an artwork. It is my driving ambition to trigger those feelings in the viewer, through my work. My works often touch on aspects of the tragic, alongside lightness and humor. I have no wish to obfuscate the darker sides of existence. I do that from a conviction that representations of the tragic can be healing. It is the age-old idea of catharsis: the identification that flows from the suffering and difficulties of (fictional) others. A novel in which everything is fine, and everyone is happy is a boring book. Whenever I read a novel, I want to be moved by depth, see how people deal with obstacles and suffering. When I go to the cinema, I want to look at the world with completely different eyes when I leave, and to have had the carpet pulled from under my feet, for a moment. You know you are not alone when an artwork gives you the feeling you are not the first to have struggled with difficulties. The artwork thus becomes a loving embrace or a consoling hand on your shoulder.

Watercolours

There is an opinion that any art is a confession or a sermon. What does art mean to you, and why is it important for humanity today?

It is a clever statement of course, that art is a confession or a sermon. But I personally think that art should notbe a sermon. Then you assume that the artist can understand life better than his viewer and is ethically superior to his spectator, and that is of course never the case. I would never want to adopt that patronizing attitude towards the spectators. As an artist I am the equal of the spectator and together with him I ask questions. I have no answers or wisdom to offer. The most I can offer is comfort and soothing calm, a feeling that we all struggle with similar obstacles and questions.

What I can agree with, is that art can be a confession, in the sense that it is always a testimony, shaped from the core of the artist’s own growing pains, personality and highly subjective view on life and the human condition.

For myself, art is first and foremost a healing force, primarily for the creator and by extension, and at least as importantly, for the viewer.

After Work

Maurice

Wunderkammer (Brian)

It is absolutely both. Just as in literature there are novels that are very accessible to almost anyone, but at the other end there are also the extremely hermetic, complex books that might only be comprehensible to the most specialized exegetes. Both have ends of the spectrum, and everything in between, have all rights to exist.

I like to make art that is both accessible to the layman, and sufficiently complex and layered to offer the seasoned art lover enough depth and essence. So, it is not one or the other, but both are extremely valuable. I believe in art for everyone who is receptive to it, as well as in the value of specialized art for which it is best to having had a form of in-depth education.

My bed a raft, the room the sea, and then I laughed some gloom in me

Dancer

Zhai-Liza (angel)

Haha, I understand your question, but when I talk about my work, I don’t like to speak in grand terms like ‘triumphs’. It’s, of course, essentially about every single viewer who tells you that they were touched by your work, that they found solace and meaning in it: that’s the greatest and most valuable imaginable.

Apart from that, in terms of public response, my exhibition at the Amos Rex Museum in Helsinki two years ago was something very special: 168,000 visitors, many of whom stood in line for two hours in the freezing cold to see the exhibition. And if there had been no daily limit, we would have exceeded 200,000 visitors.

In addition, there were symbolically important moments of recognition, for example when my film ‘Staging Silence (3)’ was shown at Tate Modern, or its predecessor ‘Staging Silence (1)’ was exhibited at the Hirschhorn Museum in Washington DC.

In addition, there are the large permanently installed and displayed works such as my life-sized nocturnal highway restaurant overlooking a sculpted night landscape, which was given its own building at the Towada Art Center in Japan, or my key work ‘The Collector’s House’, a 250 m2 work as well, which my team and I recently permanently installed at the Stiftung Kunstdepot Göschenen, a new Swiss museum.

And right now, my team and I are fully preparing for my large solo exhibition (‘Nocturnal Journey’) at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Antwerp, which will open in March 2025.

There are no reviews yet. Be the first one to write one.

A whole world on the tip of a pencil. The story of an artist who proved that true art has no limits and that it is never too late to start all over again.

International fashion icon and symbol of Parisian style, Ines de la Fressange is one of the most famous women in France.

Anastasia Pilepchuk is a Berlin-based artist with Buryat roots. She creates masks and face jewellery inspired by the nature and the culture of her beautiful region.

A whole world on the tip of a pencil. The story of an artist who proved that true art has no limits and that it is never too late to start all over again.