The transition was a bit complex — less than six months after I moved, the COVID-19 pandemic began.I found myself in a new and fascinating city, but most institutions were closed and my studies moved online. Once the pandemic passed, though, I discovered and experienced so many interesting things here.

I love London — the life I’ve built here, my friends, my partner, my work, the cultural life, the parks, and my home. Of course, I miss my family, my friends back home, and speaking Hebrew. I grew up with a Canadian father, so we spoke English— that made the shift to English as my main language feel quite natural.

I imagine my work is influenced by this transition, but not in a very conscious way. During my studies at the Royal College of Art, I made a piece about my identity as a Jewish person — something I’ve felt differently here, especially in recent years. Although I’m not religious, my minority status here is more acutely felt.

At the same time, I’ve always been exposed to other cultures — my family travelled abroad a lot, often to England, so I had some sense of where I was moving. Still, nothing could have prepared me for how big and diverse London actually is!

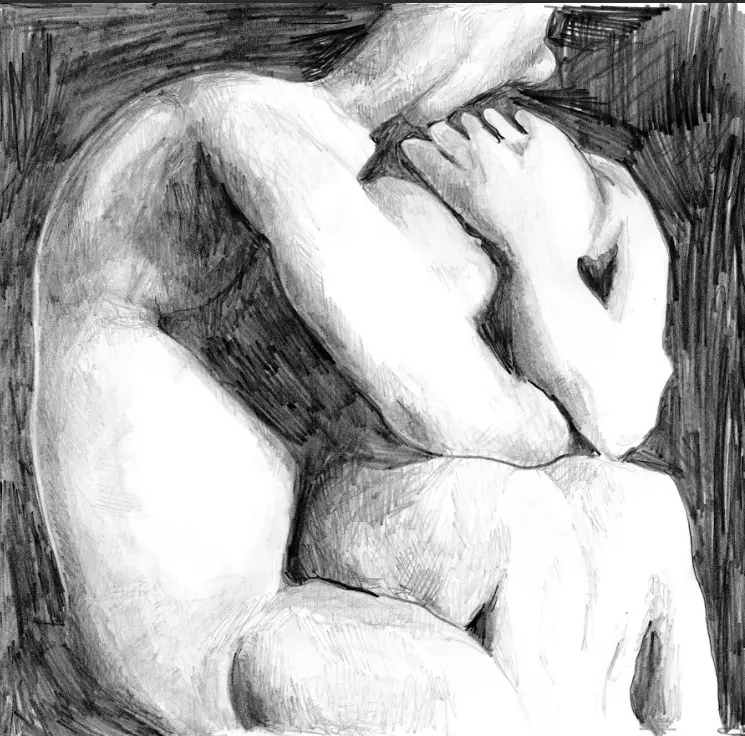

I’ve always been curious about different media and what each one allows me to express. There are two main reasons for the variety in my work:

The first is that I usually start with an idea and then think about how best to communicate it — that process naturally leads me to the most suitable medium.The second reason is immediacy. Often I have an idea that I want to get out of my head quickly, so I draw it in pencil or make a collage. Later, I might return to that same idea and develop it into a sculpture, video, painting or a kinetic piece.

The Dove of Peace, with an Incision Along Its Side Revealing the Bullets of War. I was trying to communicate my feeling of frustration, sadness and helplessness with the state of the world during these dark times.Then, I thought about this visual — it felt like it captured my feelings and thoughts. I shared it with my friends and my mother, talked about it, and read more about the representation and symbolic meaning of the dove.I wanted the visual I saw in my head to exist physically in the world, so I decided to turn it into a sculpture. I contacted a taxidermist to create a white dove for me. I made sketches and visual simulations of the pose I envisioned, so the dove could be shaped accurately while still soft.Then I searched online for dummy bullets of the right size and shape and ordered them.After that, I attached the bullets inside and around the dove so that it looked as though it was filled with them and they were spilling out.

Finally, certain parts — like the beak, claws, and eyelids — were painted, because those parts tend to fade over time, and painting them helps preserve the “alive” appearance.There wasn’t really a surprising moment during the process, but I learned a lot from it. Seeing the sculpture completed was an emotional and powerful moment.

In both of my “breathing” sculptures, movement is absolutely essential. Breath represents life. These are minimalistic works that simulate the act of breathing — without that motion, they would simply be static objects, stripped of their essence.

Let There Be Light explores dualities and wholeness — the light dims and brightens as it “inhales” and “exhales,” engaging with the relationship between light and darkness, life and death. Mnēmē deals with memory and the emotional bonds we form with objects in our lives — and how, in a way, we breathe life into them.

Every medium I haven’t tried yet is one I’m curious about. Each has its own unique qualities and expressive possibilities. I’d love to experiment with all the formats you mentioned — and more.

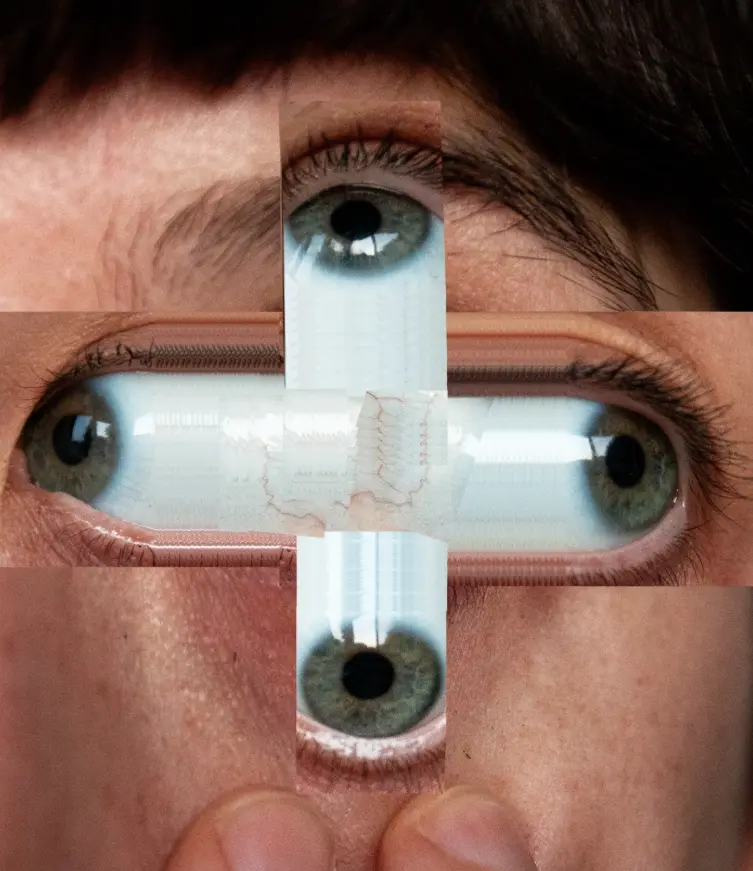

I have a strong prescription in my glasses — you could even say a visual impairment. I’ve worn glasses since I was seven, and until you asked, I hadn’t really thought of it that way — but perhaps this impairment does occupy my mind more than I realized.As the saying goes, the eyes are the window to the soul — and to the unconscious. We see the world through them, and we communicate through them: in expressions, in tears, in the crinkle of a smile. Eyes are also a symbol of higher awareness, alertness, the third eye — I could go on and on.

The Bed is meant to evoke difficult emotions. It addresses the dark realities that happen behind closed doors. It wouldn’t say one specific thing — it doesn’t tell a single story. It’s about the traumas that occur within a space that’s supposed to be safe and protective —the house, the bedroom and then the bed. These traumas can be psychological, physical, or both. The work speaks about violence experienced in the home — violence that is often hidden.

The light bulbs sculpture was created in 2024, about three years after Mnēmē. I see it as a continuation of that work.Since I was about twenty, I’ve been fascinated by personifying objects — giving them life — usually through the act of breathing.I saw in light and darkness a kind of breath.I felt I could express the idea of duality best through a light bulb that breathes — allowing the viewer to connect and resonate with it on a visceral level.

I find it hard to name just three contemporary artists that I consistently return to, as I’m constantly discovering new work that inspires me. I attend exhibitions and often find myself influenced by a wide range of artists. For example, I recently visited the Ethel Colquhoun exhibition at the Tate, which I found deeply inspiring. I’m also drawn to conceptual art and artists such as Marcel Broodthaers stimulate my mind.