Not in technical terms, but in what you’re trying to explore or express through your work. For someone discovering my work for the first time, I would describe it as an exploration of simplicity, contrasts, and transformation. I try to take everyday forms and materials and let them appear in a way that feels unexpected or unfamiliar.

My work is not so much about technical perfection, but about searching for essence-how a square, a line, or a simple surface can open up new meanings. The process of making is very important to me, because it allows the material itself to guide the outcome. In the end, I want my work to invite viewers to look again at what seems ordinary, and to discover something essential and surprising within it.

It wasn’t love at first sight. I actually entered art school with the idea of becoming a graphic designer. In the first year, everyone followed a broad foundation program, where we were introduced to different disciplines. That’s when I encountered three-dimensional work, and it immediately drew me in. I realized that working with space and materials spoke to me in a much stronger way, and from that moment I chose sculpture as my direction.

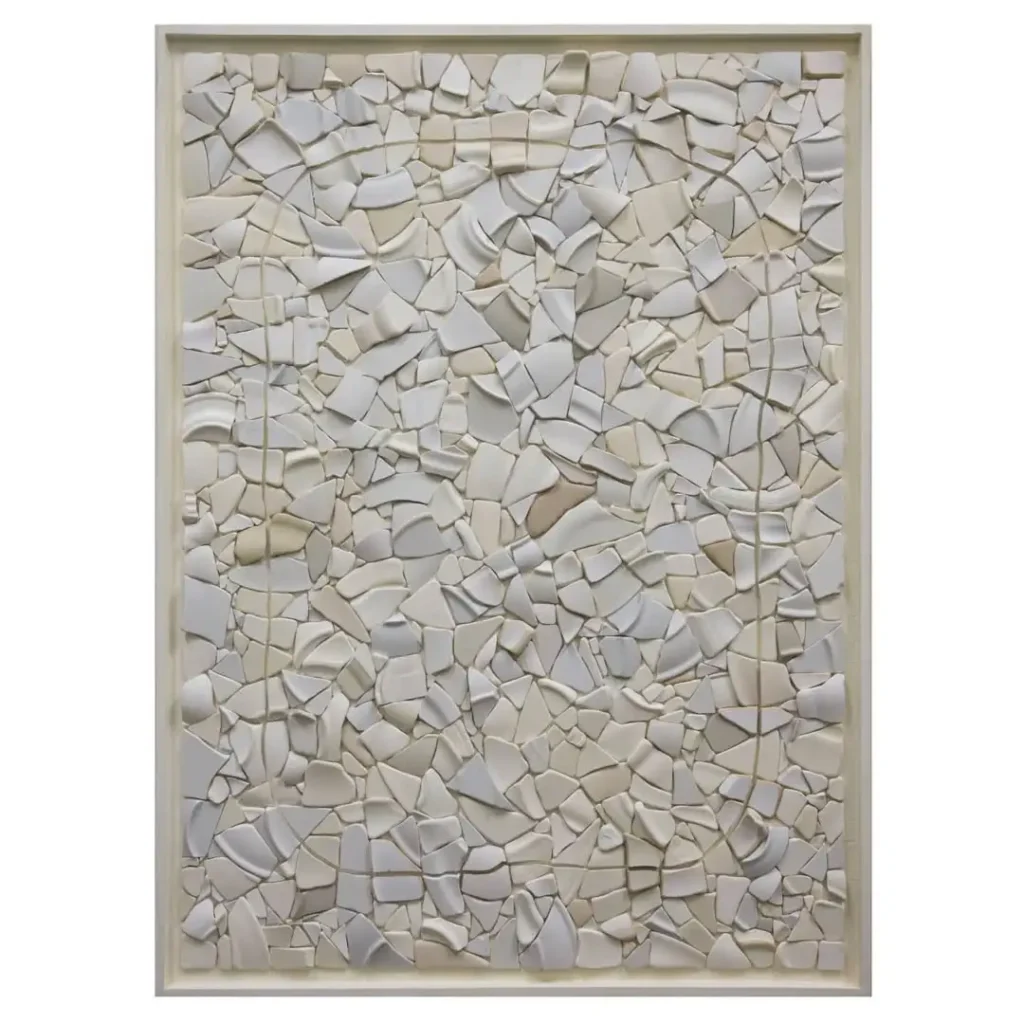

After finishing art school, I began working with black granite. It’s a material that can be polished to a perfect, glossy, deep black surface. At first, I created very minimal, precise forms, but in the process of polishing I felt I was losing touch with the raw, natural stone. To bring that tension back, I started breaking the polished forms, exposing the rough, fractured surfaces. That contrast between the smooth and the raw, the controlled line and the unpredictable break, was the first moment I understood how much more energy an “unfinished” shape can hold.

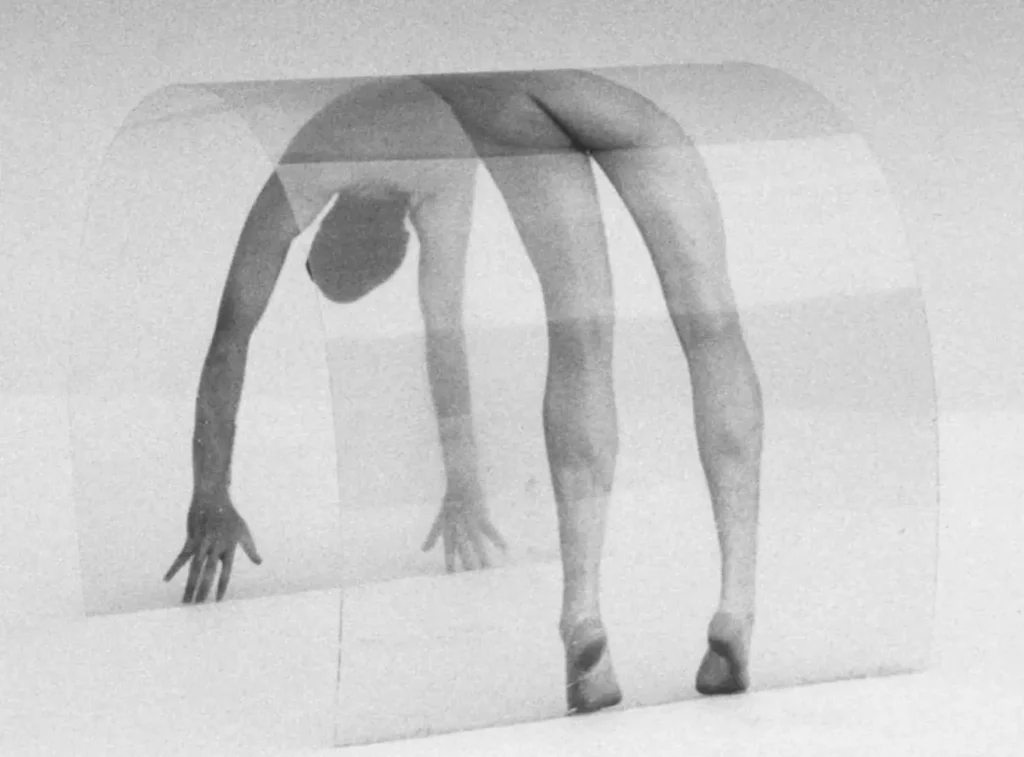

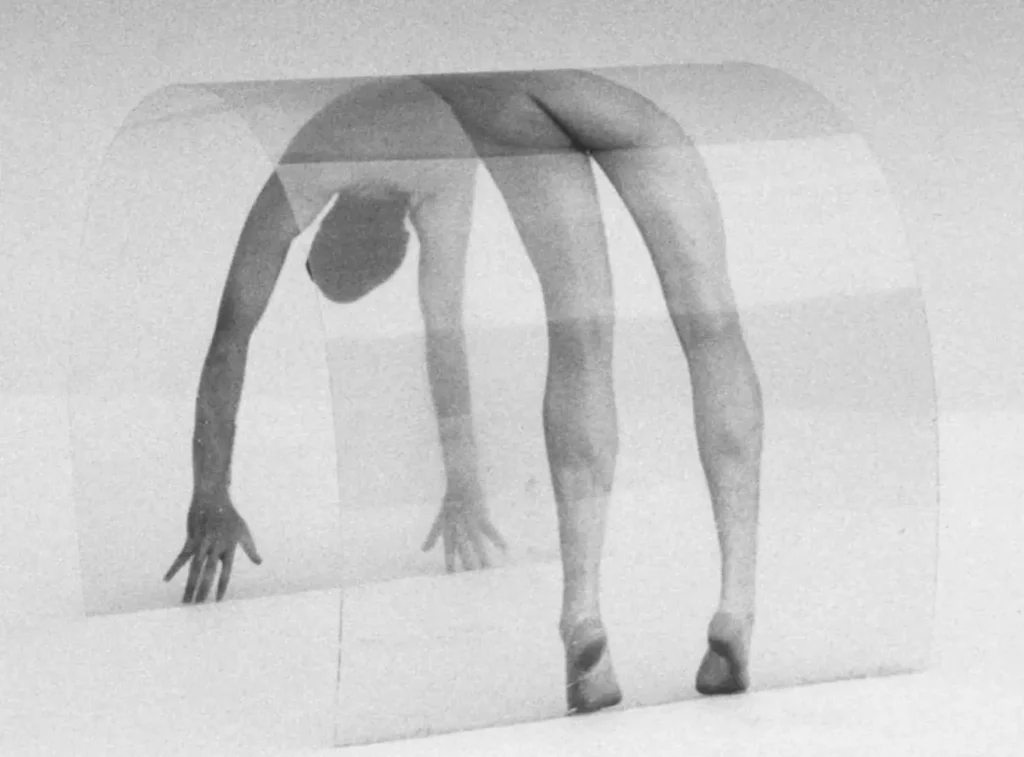

You once repurposed a graphite crucible for a rubbing technique. Can you recall the moment when you saw that industrial object as an art- making tool? Alongside my work as an artist, I have always worked in a steel factory to provide for my family. There, I encountered many new materials, most of which were discarded after use. This sparked my curiosity: I began experimenting and discovered new possibilities. That’s how my self-developed rubbing technique with a graphite crucible emerged, as well as cubes and rings made from steel strips, works with rubber, and even with analogue photographic material. Industrial waste thus became both a source of inspiration and a natural part of my artistic practice.

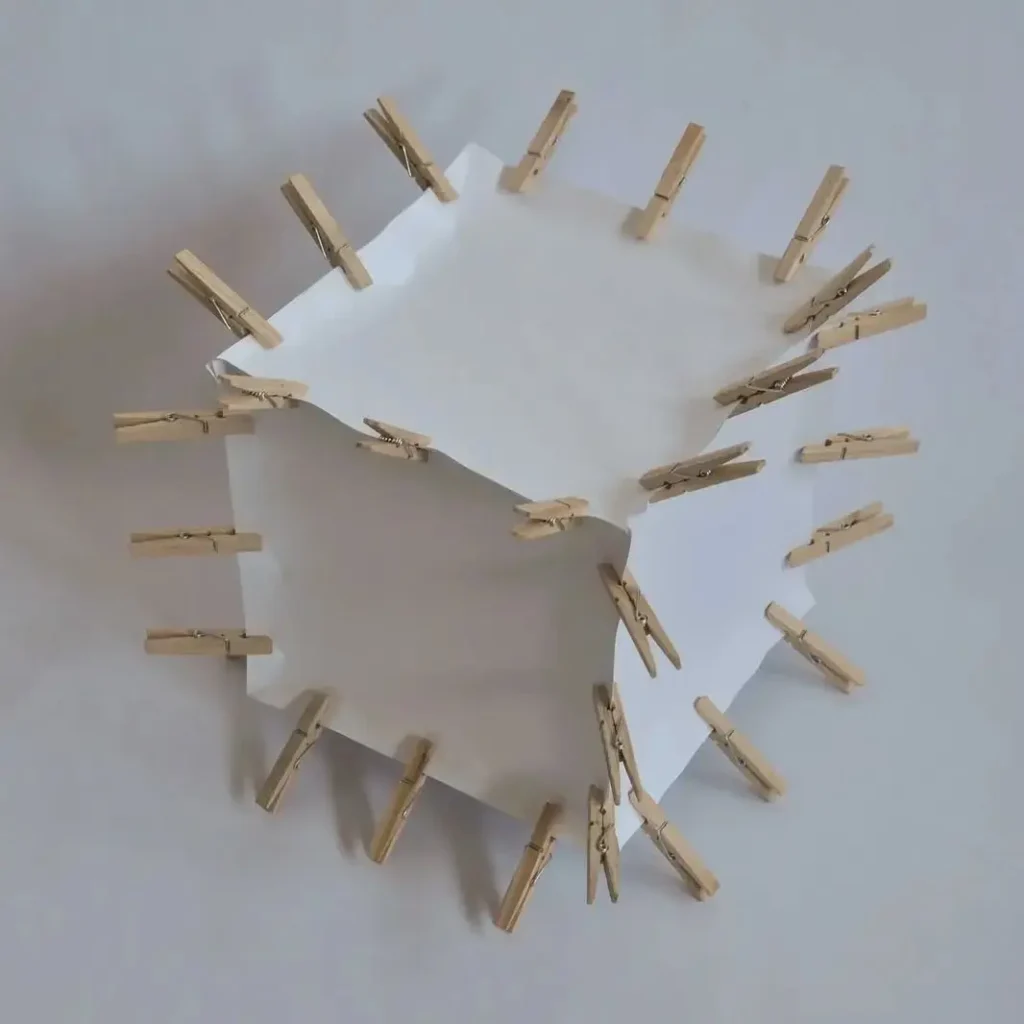

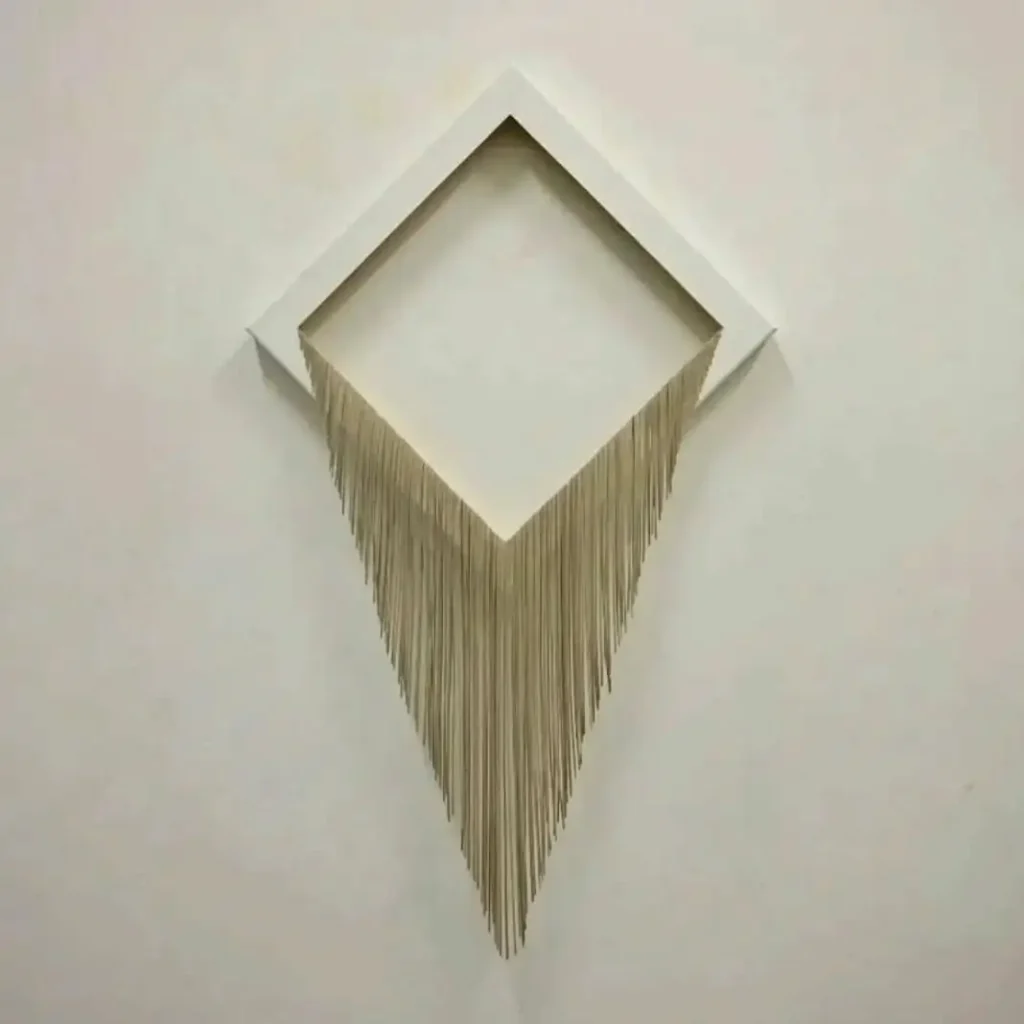

I initially wanted to cut the vertical threads of a fabric along a line and pull them back to create a square of only horizontal threads. With jute, however, the vertical threads were too stiff to fall neatly, and the horizontal ones began to sag because their tension was lost. Instead of seeing this as a failure, I used it as a starting point for a new work: by alternating the removal of vertical and horizontal threads within a glued square and its diagonals, I created layered thread patterns. As the loosened threads grew longer, I could push the center outward, transforming the surface into a three-dimensional pyramid.

This piece is my personal favorite. During my studies at the art academy (1976), I was exploring what could be done with geometric forms. I became interested in the half-cube, created by cutting a cube along one of its diagonals. Each half-cube still has two squares, and another half-cube can be placed on them in four different ways-similar to Rubik’s Snake, which appeared later in the 1980s. This led me to replace the squares with circles and connect them, creating not just four but endless possibilities. Because there were too many variations, I searched for the smallest possible chain of “half-cubes” that could still move. That’s how the rotating wooden sculpture came to life.

It really varies. The black granite sculptures I made in the late 1970s and early 1980s were very labor-intensive and often took around six weeks. For the double cubes, I developed my own technique: I split a granite cube into predetermined pieces, marked the fracture lines, covered them with a flexible glue, and then placed the pieces in a large tumbling machine with water, powder, and grit. Depending on how rounded I wanted the pieces, the process could take four to eight weeks before I removed the glue and reassembled the cube. At the same time, some works come to life in just a single day when I have a clear inspiration, while other ideas can take years- like the three cubes of wood with annual rings, which I could only realize after finally finding the right wood and the right saw.

No, there aren’t really materials I still wish to work with that I haven’t tried yet. I’m a collector by nature and often browse thrift shops to see if something catches my eye for future works. Recently, I picked up a large number of small cylindrical and cubic magnets, as well as two huge mirrors. I’m fascinated by the way the magnets attract and repel each other, and while it may take time before these finds become part of a piece, I enjoy experimenting with them in the meantime.

Most of my ideas are visual, but sometimes they come from something I hear or read. These days, I also find inspiration online. And often, the act of making one work naturally leads to new ideas.

I’ve never really struggled with creative blocks. Creativity doesn’t just appear-you have to get to work and let it grow through the process.

Yes, it is personal. The themes of tension, balance, and deconstruction reflect the way I experience life itself-how things can shift, fall apart, or find stability again. While my work is abstract, it always carries something of my own search for harmony within constant change.

I create my work primarily for myself. I try to keep it as simple as possible and express the idea in its most essential form. From there, the viewer is free to interpret it in their own way.

If an idea works well on a small scale, I realize it that way. But if it comes across more strongly on a larger scale, then I choose to execute it in that form. Scale also changes how the viewer experiences the work-small pieces invite closer, more intimate attention, while larger ones create a physical presence that can surround or even confront the viewer.

I have already created several public artworks, all autonomous sculptures in black granite. They are placed in locations such as a town square, a cemetery, and along the street. Working in public space brings different challenges than in the studio: the work must be accessible to everyone, able to withstand weather conditions, and resistant to vandalism. That is one of the reasons I often chose black granite-it carries a strong physical presence while also being extremely durable.

Interestingly, I’ve just done a project that was completely outside my comfort zone. Each year my town organizes an exhibition called the “Shop Window Art Route”, where local artists show their work in store windows. I had never participated, because I felt my artworks don’t really come across in that setting. But this year I wanted to present myself to the community, so I created a work entirely from QR codes linking to my website, Instagram, and YouTube. QR codes are built from small squares and is a square, which connect naturally to my recurring theme of cubes and geometry. I designed a large composition of nested squares, from one big square down to progressively smaller ones, filling a window of 207 x 173 cm. In the end, the piece contained 705 QR codes-after much testing to ensure they were still scannable at different sizes. It was both a technical challenge and an exciting new way to translate my ideas into a completely different medium.

Yes, I curate it myself. On that account, I share the art and things that speak to me and serve as inspiration. For me, it’s a way to give insight into the sources behind my own work and to show how ideas can grow from many different places. It’s also a way of connecting with others who might find inspiration in the same things.